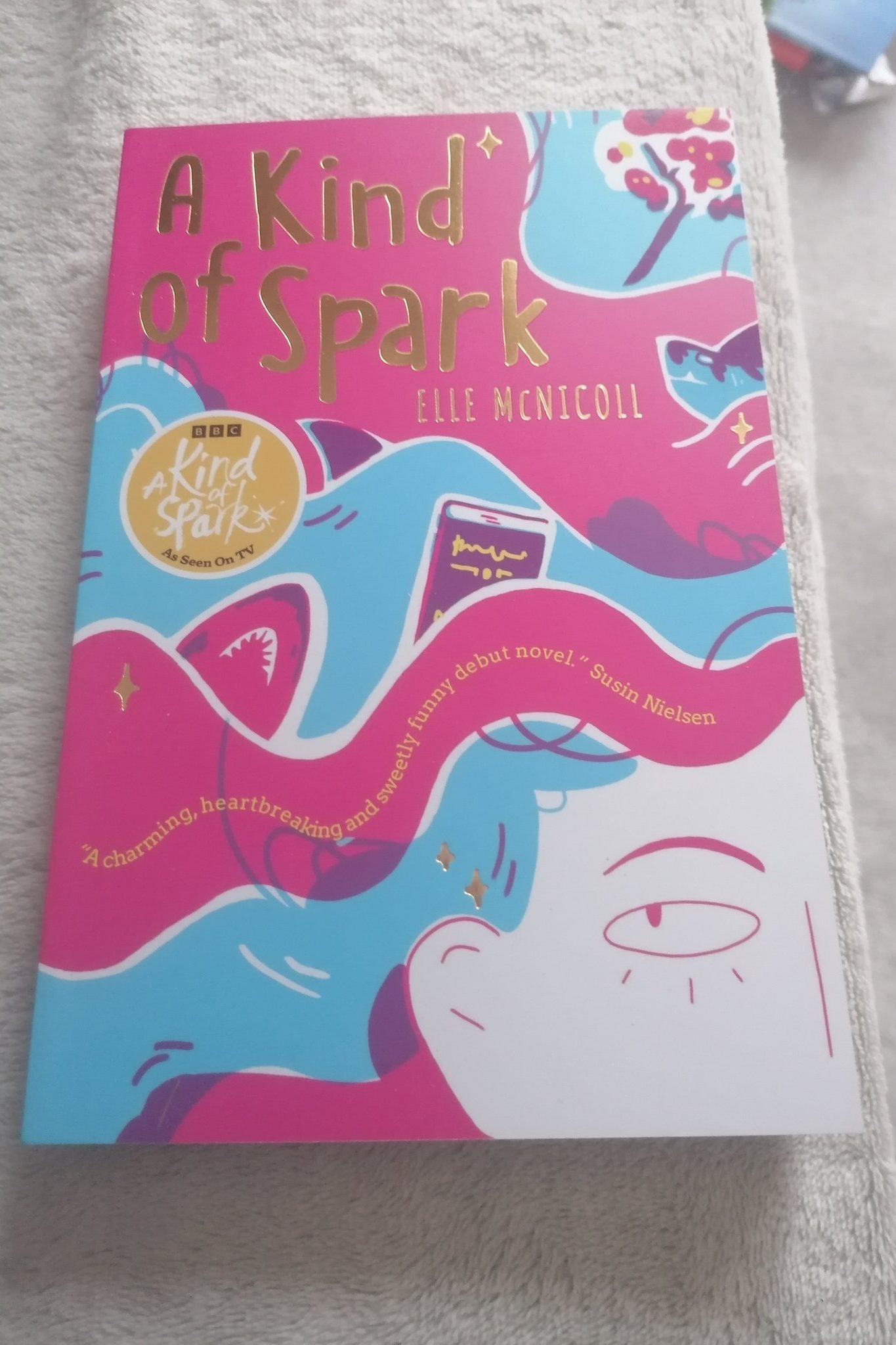

A Kind of Spark by Elle McNicoll – A Personal Reflection

I started watching the CBBC dramatisation of A Kind of Spark last week and pretty much instantly bought the novel. I am of the opinion that good novels are good novels, whoever the target audience are. For many years I read to my children at bedtime, and in those years I came to the conclusion that some of the most enjoyable reads were to be found in the YA section. Unfortunately, YA books have been all too easily dismissed as a result of that label, rather like the romantic comedies written by female authors and aimed at a mainly female audience – I refuse to use the frankly insulting term used to dismiss them. I am, as it happens, a huge fan of books by such authors as Sophie Kinsella and Cecelia Ahern amongst others. So, what did I think of A Kind of Spark when I read it?

The Autism Experience

Well, I can only start in one place, the portrayal of autism from someone who can understand the experience intimately. Elle McNicoll is on the autistic spectrum, like myself, and it definitely shows. I thought I knew a lot about my own experience with undiagnosed Asperger’s, but I had only scratched the surface as it turned out. All I had done was to read about the views of Neurotypical (NT) researchers who could not hope to understand what goes on inside an autistic mind. So much fell into place when I started reading it. My initial fascination with history and with dates and the encyclopaedic knowledge I stored up about it is reflected by Addie, the central character, and her fascination, first with sharks and then with witches. Like me, her mind worked overtime when focused on a subject that interested her, but failed to work effectively in areas that didn’t. When I was at school I was very good at English and History, but struggled with Mathematics and Science. Like Addie, my handwriting was abysmal at first, although I trained myself to write in a very neat hand. I’ll come back to that later. Due to my dyspraxia my motor skills were very poor, which was most obvious in sport, art and design and technology. I used to dread all those lessons because I knew I would fail at them. This led to me having flashes of frustration and temper, another thing I will return to. Finally, like Addie and her sister Keedie, I was, as Addie points out near the end, very easy to bully at secondary school in particular and that made my entire seven years miserable, particularly as it came from the staff as well as the other pupils. In those days, I was always told to ‘pull myself together’ and to ‘deal with it like a man’, both at home and at school. It led me to withdraw into myself as that was the only place where I could find any respite.

When you read about autism from an NT perspective, the characters are automatons with little understanding or inclination to display or understand emotion. Now, that may be the experience of one section of the autistic community, but Addie’s experience of heightened emotions, heightened reactions and heightened impacts was finally my experience told in a way that chimed exactly with what I felt. This is why music can have such an effect on me, because I can end up living a song in a way that is as intense as anything I experience in everyday life. It explains why certain characters in books, TV series and films can have such a huge effect on me. This dichotomy between the NT view of autism and my own experience confused me until I started reading this book.

Coping strategies

As Addie says towards the end of the book, those of us on the Autistic Spectrum have to live in a world that isn’t built for us. As a result we fall back on certain strategies to deal with situations that we cannot fully understand throughout our childhood and indeed into adult life. Before reading this book I had heard of stimming, which are calming physical actions that help to bring your mind back to some state of equilibrium. I was aware of certain repetitive actions and behaviours which I indulged in, but these were always presented negatively by the NT people in my life. I was told I was weird or told to grow up so I tried my best to ignore my need to use that approach and ended up causing myself far more stress in the short and long run. If I did indulge in the behaviours it was in the safety of my own room and with a sense of guilt.

The next strategy, which I had not heard of, back in the darker days of my childhood where no one wanted to understand the ‘weirdos’ – I was called much worse, for example by other kids and even a teacher who referred to me by a term routinely used to describe people with cerebral palsy – purely because no one cared. Anyway, the strategy was masking. Masking is where the autistic person tries to mimic the behaviour of those around them in a vain effort to fit in. When I started to read about masking from a non NT perspective, elements of the last 50 years of my personal and social development finally fell into place. The way I constantly fought against my own instincts at home, at school and with friends was explained, as was the sheer exhaustion of having to do so, minute after minute, day after day, year after year. Keedie, Addie’s older sister, doesn’t tell anyone at the university she is at that she is autistic because she wants to make a fresh start. Eventually the effort completely exhausts her. I read this and remembered a three week stretch in my second year at university where I could barely get out of bed and I certainly couldn’t face anyone else. I stayed in my room, too exhausted to study or socialise, recuperating until I felt ready to face the world and mask again. This happened over 30 years ago, and at the time I had no idea what was wrong with me. Thanks to Elle McNicoll I do now – nothing! After so many years of practice I am now quite adept at masking, but the payback is that most weekends and holidays I spend a fair proportion of the time trying to recover from the mental effort that may be, apparently, less onerous as a result of experience, but which is definitely cumulative.

When you cannot mask any longer and someone does something so bad that you can’t control yourself you can end up having a meltdown. In a way, it’s another coping strategy, but it is definitely not one you want to resort you, it’s one you end up having no choice to resort to because you ‘snap’. In a world where NT people, often consciously, like to push you to that point, it’s a wonder it doesn’t happen more often. If I meltdown it tends to be verbal rather than physical, but I will also just walk away from a situation and keep walking to try to put mental and physical distance between myself and the situation. The reality of Addie’s situation is that her meltdown is met first with laughter and then with retribution by the NT world who pushed you there in the first place. On the couple of occasions I got physically aggressive, like Addie I was the one blamed and the one punished.

This book is apparently the most read book by Scottish secondary school pupils. All I can say is that if the NT students are educated and the students with one of the forms of autism are reassured by this book or the series, then it will be a huge step in the right direction. Thank you Elle McNicoll for opening the door for us, but to the NTs who might read it, please warn us before you come in as we don’t like surprises!

Discover more from David Pearce - Popular Culture and Personal Passions

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks